Spatial Embeddings for Model-Based RL

One of my favorite quotes of all time is by the famed science fiction writer Arthur C Clarke: “Any sufficient advancement in technology is indistinguishable from magic.” I think it provides an interesting perspective on everything from current technology, like email, to futuristic technology, like brain-machine interfaces. While the topic of this post isn’t at that level, when one of the PhD students I knew at Berkeley showed me this idea for the first time, it took my breath away like an astonishing magic trick. With that in mind, I’m going to set up this blog post a bit like a magic trick. First I’m going to explain the setup and show the results. Then, if you’re interested, you can keep reading and figure out how it’s done. For the sake of brevity, I won’t go into an insane amount of technical depth. Instead I’ll focus on the high level ideas of what’s going on. However I’m making all the code publicly available, so the enthusiastic reader can always look there for the nitty gritty details, as well as the references I list. As always, you can also reach out and ask me any questions you may have.

The link to all of the code is available on GitHub here. While all of the code is my own, it’s worth mentioning again that the idea for this was from a neuro PhD I knew at Berkeley.

Setup

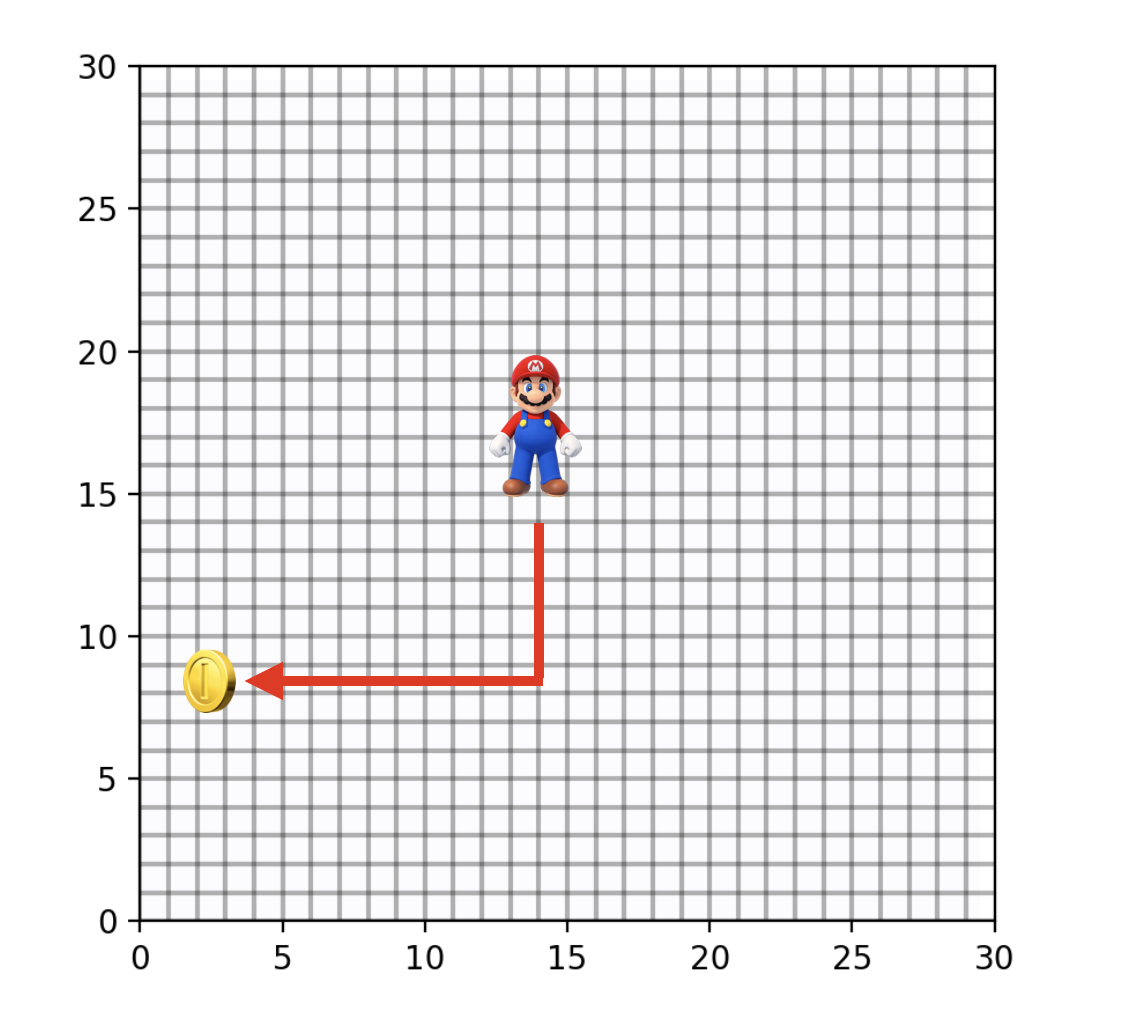

In reinforcement learning (RL) there is a set of classic environments called Grid Worlds that are exactly what they sound like: simple 2d grids that an agent can navigate by moving up, down, left, or right. For example, take a look at the environment below, where the Mario icon represents the starting point for the agent and the coin represents the goal destination. If all things are equal, then the agent can get there efficiently by using 17 steps: 7 down and 10 to the left.

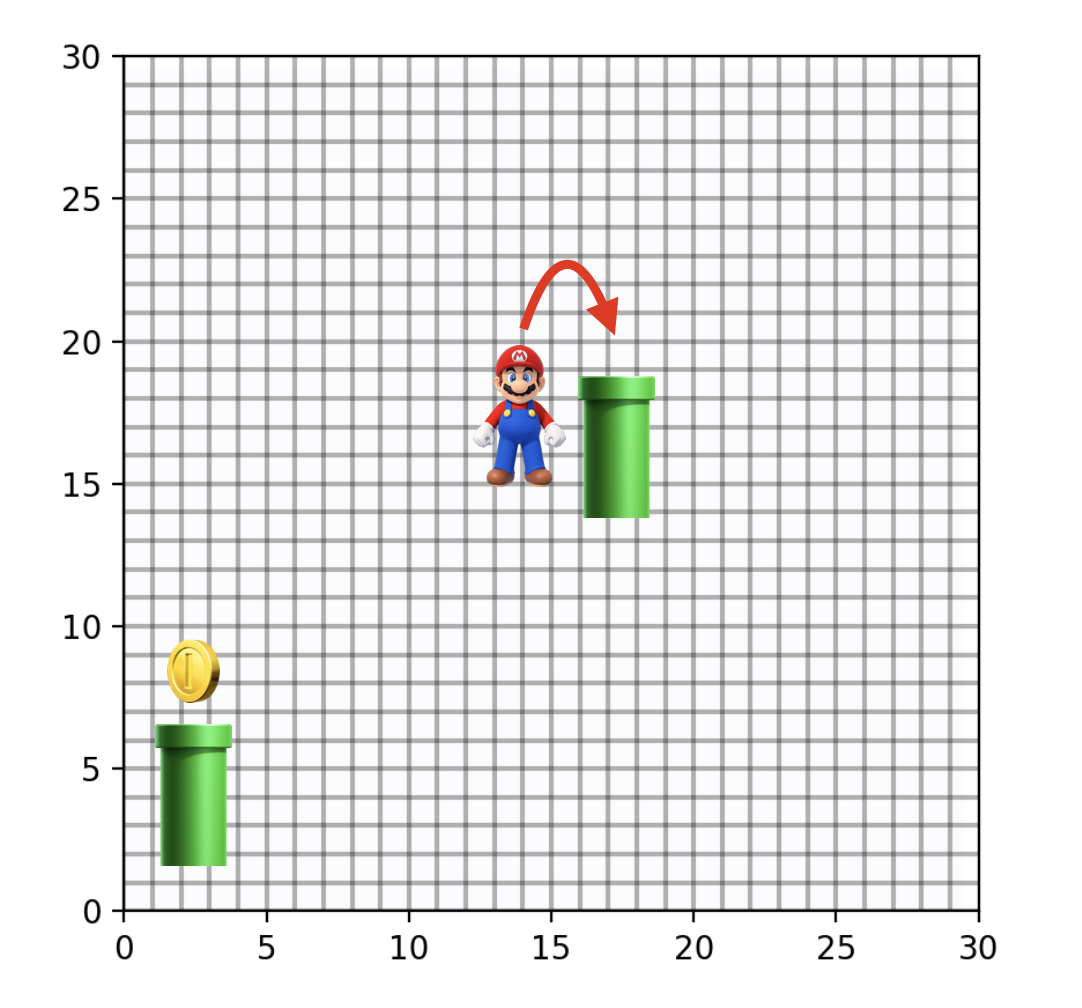

But what if all things aren’t equal? What if we introduce a mechanism that teleports the agent from one location to another? For example, there’s the classic pipe from Mario games. How does this change the optimal behavior? Well, depending on where the agent is, it may be more efficient to use the teleporter than to take the same path as before. So now the best path in the Grid World may look a little bit more like this:

Nothing about this is particularly special yet. Of course you could use classic RL algorithms that will be able to navigate this simple environment. They will learn a policy for the best action in each different square on the grid. But can we do something more interesting than that?

Reveal

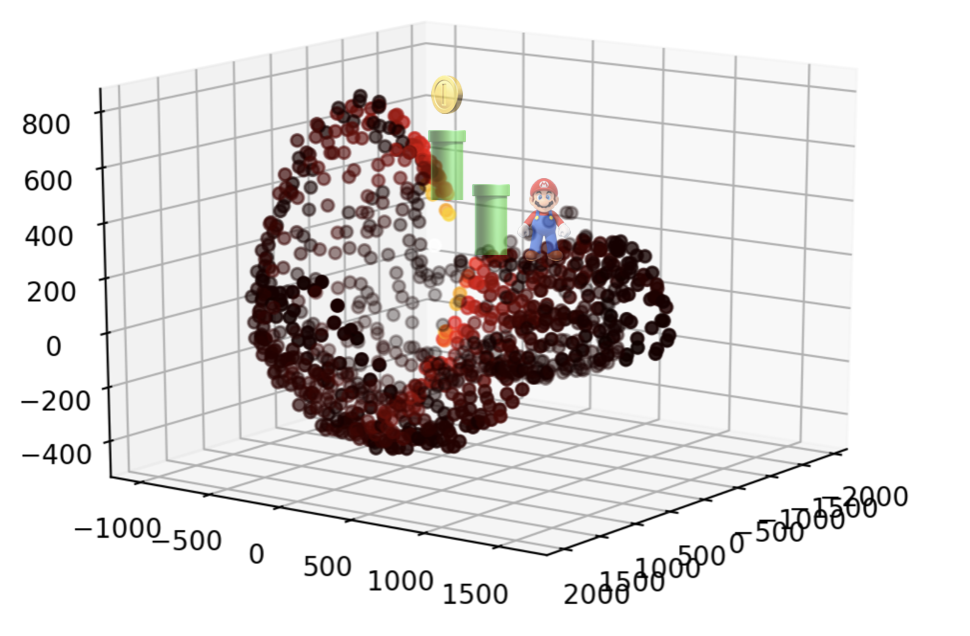

Now comes the cool part. Using the methods describe in the following section, the agent can learn a policy that doesn’t just determine the best action from each square, but actually builds a representation of spacetime that mirrors what actual teleporters (wormholes) look like, at least to my limited knowledge. You can see this by the two teleporter points folding the representation of spacetime on top of itself so that they end up almost connected in the same way that a wormhole folds spacetime. This is also indicated by the color of the points on the plot, where warmer colors indicate nearness and cooler colors indicate distance. This was, and still is, one of the coolest photos I have ever seen. Check it out below.

What’s going on here? Our agent is learning that spacetime in this Grid World is not flat. The teleporters quite literally bend the representation of spacetime so that the two teleporter locations are next to each other. Why does it do that? Well, because they are! Even though the teleporters seem far away from each other on the grid, since Mario can get from one teleporter to the other in a single move, Mario is learning that they are effectively next to each other. In order to accomodate this into the learned representation, spacetime has to literally fold on top of itself. Pretty cool, right? It doesn’t just stop there. You can tweak some parameters of the setup to get other interesting results. One of my favorites reminds me of a black hole and is shown below.

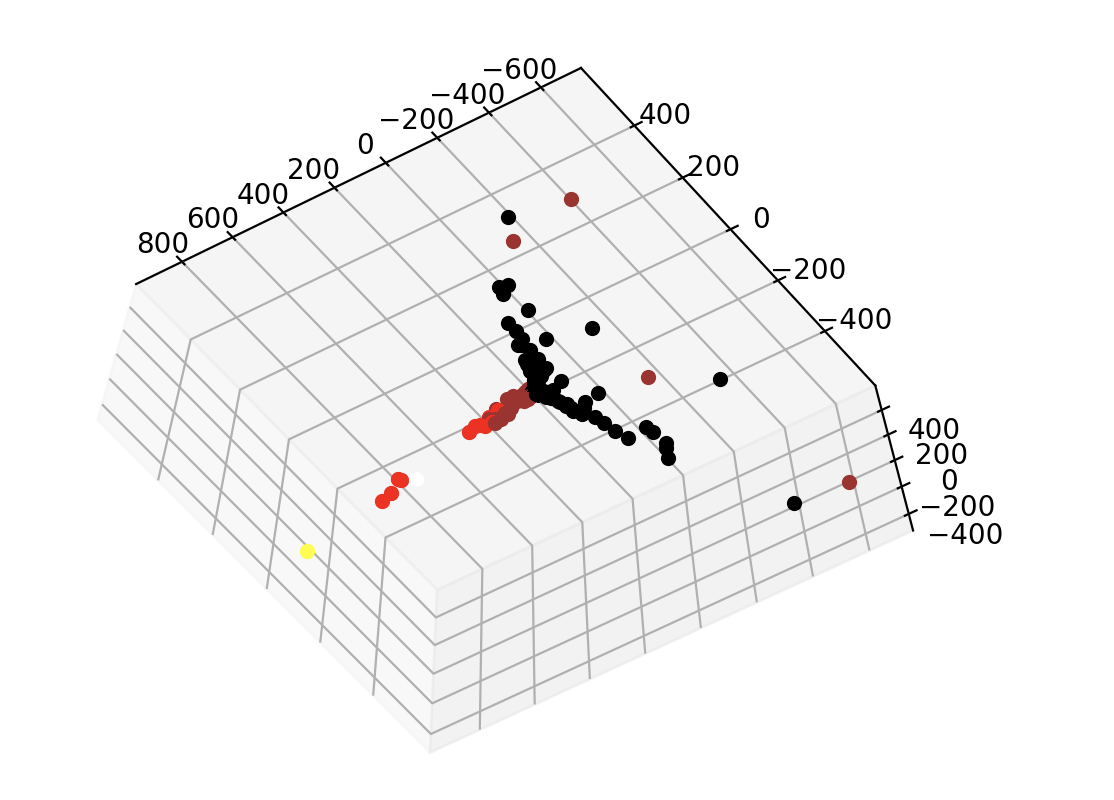

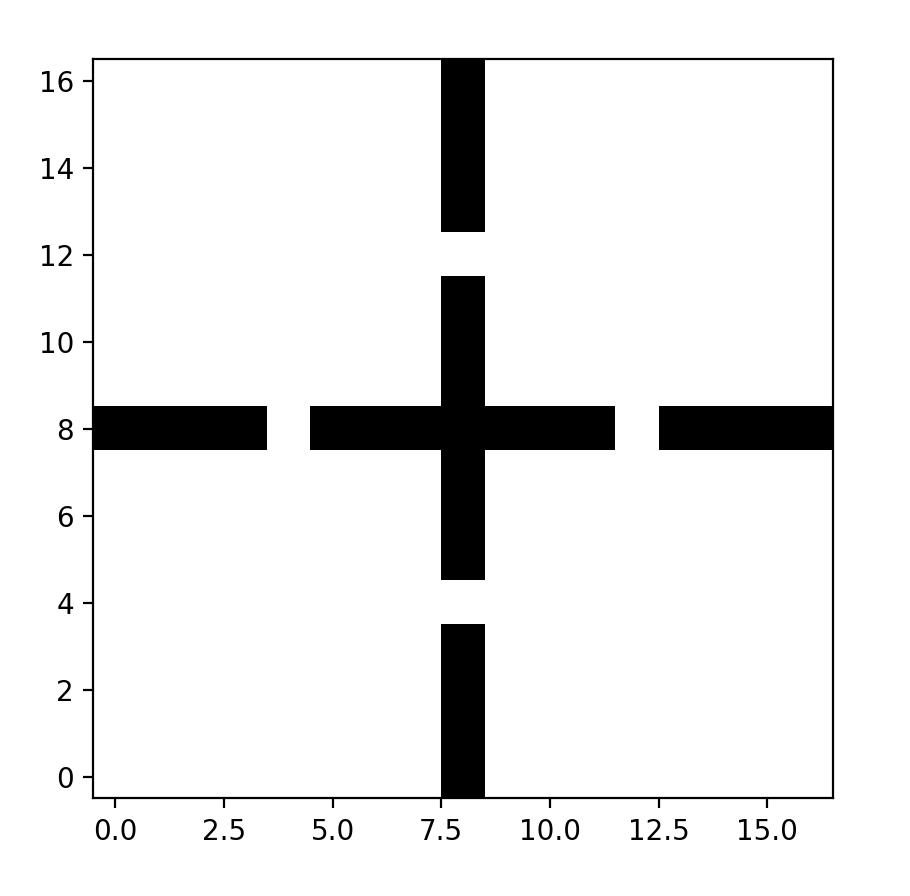

I also played around with this idea for other environments. One environment that I was particularly interested in was the four-room environment, which is a pretty simple environment used a lot in Hierarchical RL research. It has the same set up as the simple (no teleporters) Grid World, just with four rooms and connecting “doors” (the holes in the walls).

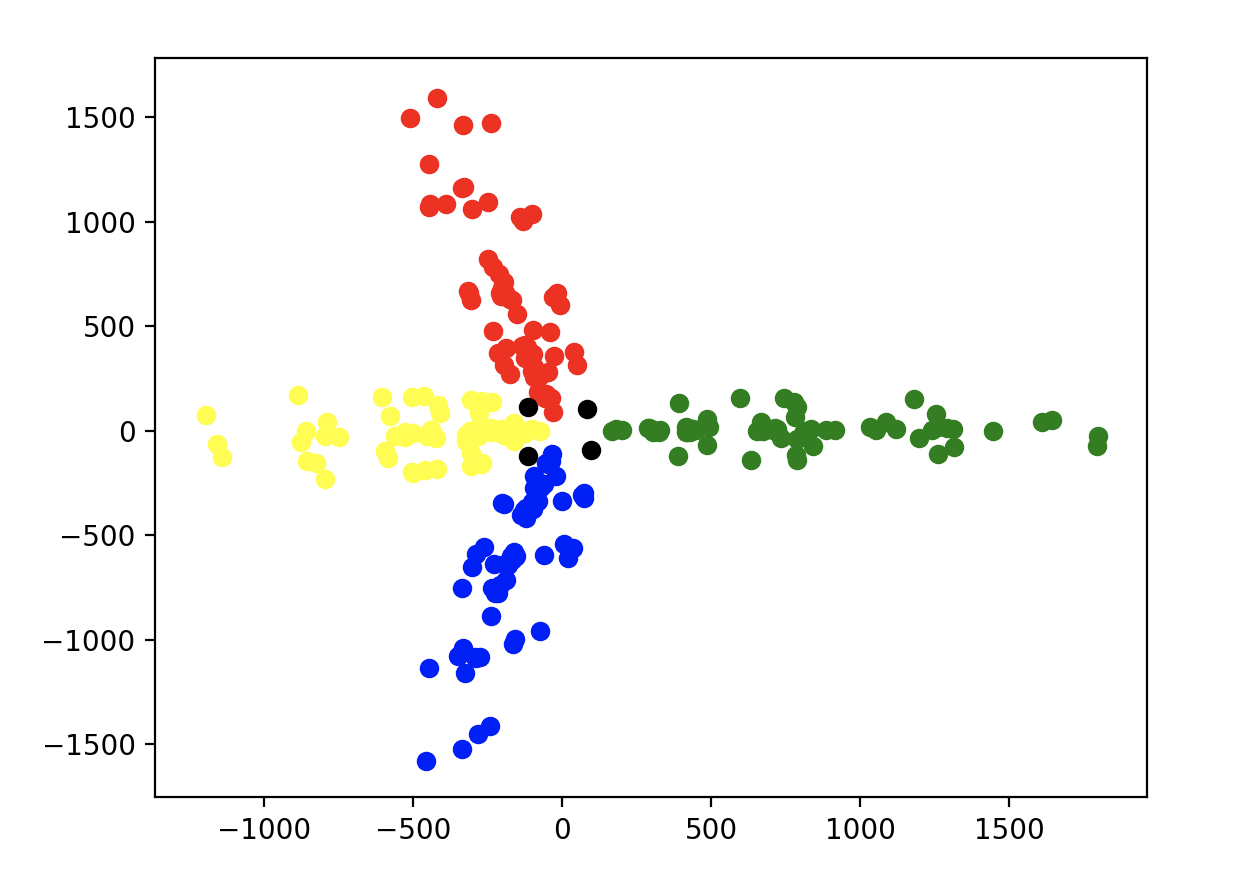

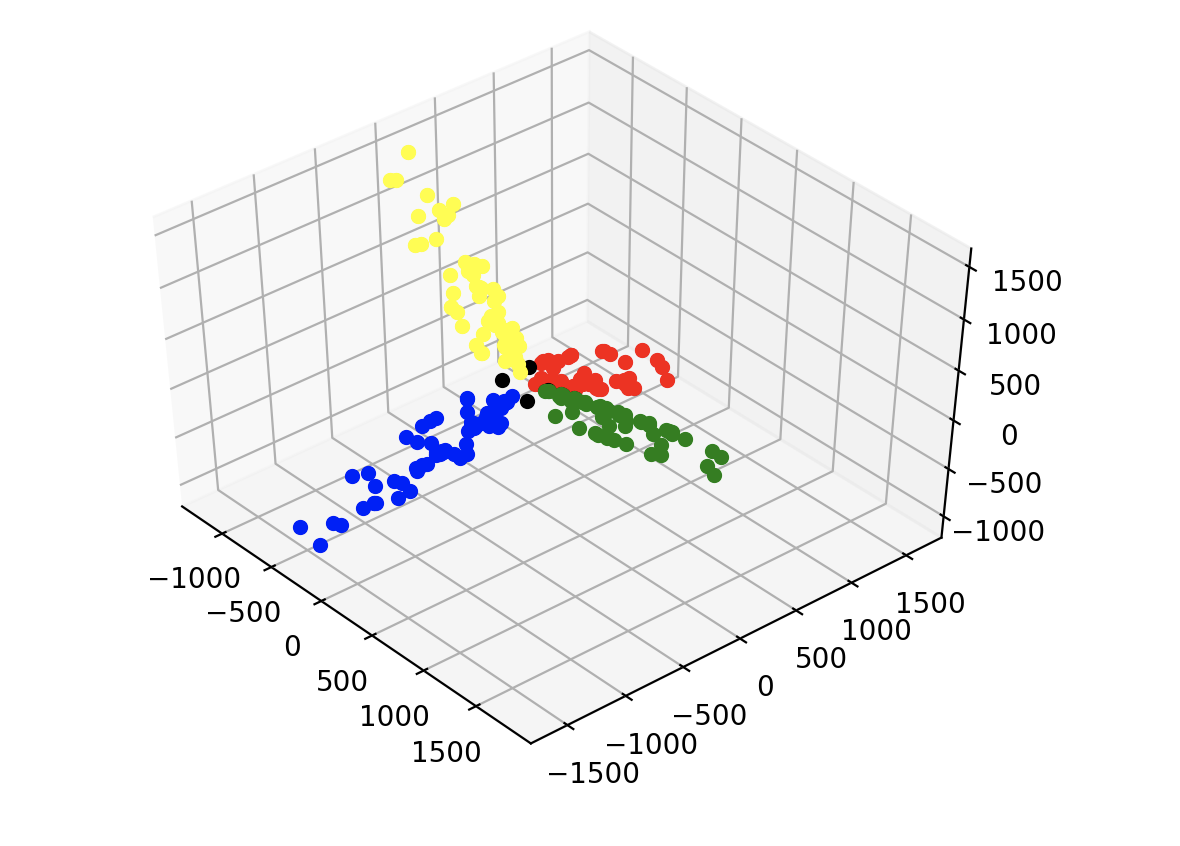

Using the same methodology, you get some interesting results. The learned representations of each coordinate in each room group so that there are four distinct groups of points. This is shown in the plots below, where each color represents a different room. Further, these groups are orthogonal to each other but symmetric to one another. All of the coordinates in the rooms fall into one of these four groups except for the doors, which are shown in black. They are generally equidistant between the point clouds at about a 45 degree angle, indicating an understanding that the doors serve as transitory points between rooms. All of this is more obvious when you can actually interact with the 3d plot in the code, but I haven’t gotten around to figuring out how to embed that in this post.

While this didn’t blow me away in quite the same way as the teleporter results did, I still find it rather interesting. I had some ideas for graph clustering to see if I could do anything fun with hierarchical RL, but haven’t yet come up with anything noteworthy.

How it works

Where science decidedly breaks from magic is the magician’s code. After all, the most important part of any experiment is arguably a replicable set of instructions. So how does this all work? What are the ideas behind the scenes that allow this to be pulled off?

Background

There are quite a few different ways to potentially understand this, such as through the lens of a graph embedding via random walks. But my goal is to make this fairly accessible, so I’m going to take a different route for explaining it that I think more people may be amenable to. Conveniently, this was also the way I learned about it originally.

For this, we must turn our attention to the realm of natural language processing. Roughly speaking, this is the idea of having computers understand language. That is a very broad statement that many people, including myself, have jumped into without thinking about hard enough. But to go any further than that opens a bag of worms that would be a long rabbit hole to go down (I talk about it for a few minutes in my guest lecture though, so feel free to check it out there). So for now, we’re going to specifically focus on one aspect of the broad idea of understanding language: word embeddings.

Word Embeddings

What is a word embedding? Let’s start with the second word in the phrase, “embedding.” This just means that we’re going to represent something as a vector. To do this, we embed that particular thing in a vector space, hence the name. Now let’s tackle the first part of the phrase, “word.” This is just telling us what we want to embed in the vector space. So we’re going to represent words as vectors. Why would we want to do this? Well, computers as we make them have a hard time understanding language. Sure, you are reading characters on some screen right now, so clearly they can display the words “dog” and “cat.” But they have no underlying idea of the relationship between dogs and cats, it’s just ASCII characters that are ultimately represented as binary. When we embed words as vectors, there are convenient frameworks that we can use to compare them and understand the relationship between words.

In order to embed words as vectors, we first have to figure out how to define a word. This seems like it should be a simple enough task, but think about how you would define the word definition. Words are defined by other words, which are defined by other words, which are defined by other words… it’s turtles all the way down. This leaves us in a peculiar and moderately amusing situation. There is a pretty deep history within this issue, and we will focus on one particular answer called the Distributional Semantics Hyptohesis.

The broad idea behind the Distributional Semantics Hypothesis is that words that occur in similar contexts have similar meaning. That’s useful, but what exactly is a context? It depends who you ask and what you’re trying to do. It could be the same few words, the same sentence, the same paragraph, or even the same chapter. For instance, consider the sentence, “In order to get to the coin, Mario jumped into the pipe.” Here the context for the word “Mario” could be the words directly next to it (“coin” and “jumped”), the entire sentence, or even this entire entire paragraph. However most often the context refers to the couple of words directly around word we are interested in. This allows us to form an understanding of a word in a way that is useful for comparing it to other words. To see this, consider swapping “Luigi” in for “Mario” in that sentence. It should roughly make the same amount of sense, so we would expect our learned represntations to be highly similar. Since Luigi tends to also jump around and find coins, this should end up being the case!

How can we use this hypothesis in a way that makes sense to a computer? There are a couple of answers to that questioin, but we will focus on one called Hyperdimensional Computer (which is also called Vector Symbolic Architectures). For a more extensive background of this field, check out this great paper [1]. The general idea is to use principles of neural architecture in order to design a computation system that is more akin to the brain. This includes ideas like population coding, sparsity, and robustness. Within the context of the current problem, what it means is that we are going to create these embeddings using a fairly simple two-step algorithm.

The first step is to generate two sets of vectors: the label vectors and the semantic vectors. The label vectors are going to serve as fixed representations of a given word, and the semantic vectors will act as our learned embeddings. Every time we see a word in whatever text we are reading, what we will do is take the semantic vector of the current word and add to it the label vectors of all of the words around it. So for the previous example, that would involve adding the label vectors for “coin” and “jumped” to the semantic vector for “Mario.” Then you just repeat that over the course of the entire text, and there you go, you have embeddings! Why does this work? It takes advantage of some nice properties of random projections and the central limit theorem that you can check out in these papers [2][3], but at a high level, just think back to the Distributional Semantics Hypothesis. We’re just finding a way to programmatically write that in a way that makes sense to a computer.

Spatial Embeddings

How does this tie back into the origina idea? Instead of words in a text, consider each coordinate space in the grid as a unique word. The text then becomes all of the coordinates in the paths that the agent takes when we spawn them at a given coordinate and let them randomly walk around for a fixed amount of time. Just like two words occuring in the same sentence are more similar, the more two coordinates occur within the same walk, the more similar they are! This makes sense for coordinates like (3,4) and (3,5). After all, they’re right next to each other. But the real trick is with coordinates that may not appear to be right next to each other to the naked eye but actually are, such as the teleporter locations. Since each teleporter location takes Mario to the other teleporter, they are effectively next to each other. Our model will learn this in the embedding, and when we visualize it in three dimensions, that shows up as the folding of spacetime! The keen reader may notice that I skipped over how exactly we go about visualizing these embeddings in three dimensions since they are actually many more (for this particular example they are thousands of dimensions). That involves an idea called manifold learning that I will leave for another time, but here is a good resource on the topic for anyone interested [4].

That’s it! That’s all it takes to pull off this particular trick. Is it cooler now that you know, or has the magic disappeared…

[1] Hyperdimensional Computing: An Introduction to Computing in Distributed Representation with High-Dimensional Random Vectors

[2] Random Indexing of Text Samples for Latent Semantic Analysis

[3] Permutations as a Means to Encode Order in Word Space

[4] A Global Geometric Framework

for Nonlinear Dimensionality

Reduction